Patient profile

Thirteen patients with MOE were treated at the university clinic of LMU from 2009 to 2020 (see Table 1). Ten of the patients were men (76.9%), and three were women (23.1%). The average age of all patients was 79.9 years, with a range from 63 to 90 years. The average age of women with malignant otitis externa was 84.3 years; the average age of men was 78.6 years. All of them received inpatient treatment. The average hospital stay was 26.2 days; two patients had two or more hospital stays during their treatment. Twelve of the thirteen patients had documented type 2 diabetes (92.3%). Information concerning type 2 diabetes status was not provided for one patient. Disease monitoring via HbA1c was performed in eleven of the twelve patients with known type 2 diabetes. The average HbA1c value was 8.35%, with a range from 6.7 to 11.6%. The type of diabetes therapy was documented for seven of the twelve patients: six patients received insulin, one patient received metformin, and one patient received sitagliptin. One patient who received insulin needed dialysis due to diabetic nephropathy. None of the patients with documented insulin therapy received combination therapy with diabetes medication.

Symptoms

Otalgia and otorrhea were documented in all patients at their first hospital visit. Facial nerve paralysis was documented in seven out of the thirteen patients. The severity of facial nerve paralysis was °II after the classification of House-Brackmann20 in one patient, °III in one patient, and °IV-V and °VI in two patients each. One patient experienced further cranial nerve paralysis during the course of the disease, namely, of the vestibulocochlear (VIII) and vagal (X) nerves.

Clinical and diagnostic findings

Inflammation parameters were moderately increased in all patients (c-reactive protein 0.7–5.9 mg/dl). One patient had severely elevated C-reactive protein (11.9 mg/dl)

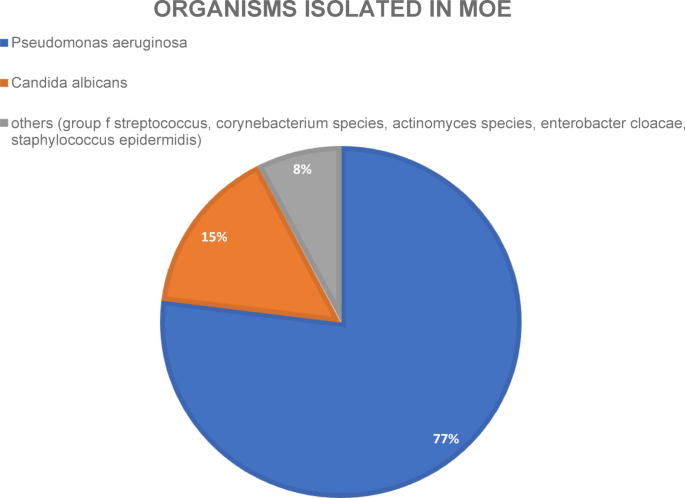

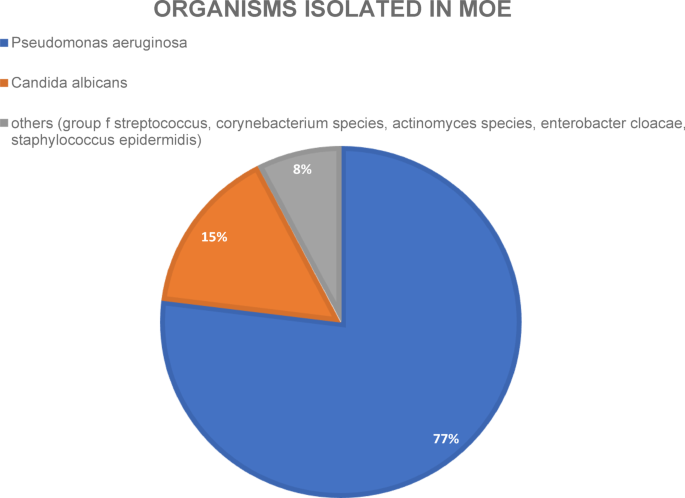

Pathogen spectrum: Microbiological diagnostics via ear canal swabs were performed for all patients. Among the ten out of thirteen (76.9%) positive swabs, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the most common pathogen. Eight out of the ten Pseudomonas infections were coinfections (P. aeruginosa + Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa + Enterobacter cloacae complex). The second most common pathogen was Candida albicans, with three positive swabs. In one of the three swabs, Candida was the only pathogen found, and the other two swabs showed coinfections (Staphylococcus epidermidis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa). One microbiological swab detected three different pathogens: a hemolytic group of streptococcal bacteria21, Corynebacterium species and Actinomyces species (see Fig. 1).

Pie chart of organisms isolated via wound/ear canal swabs of all patients of this study.

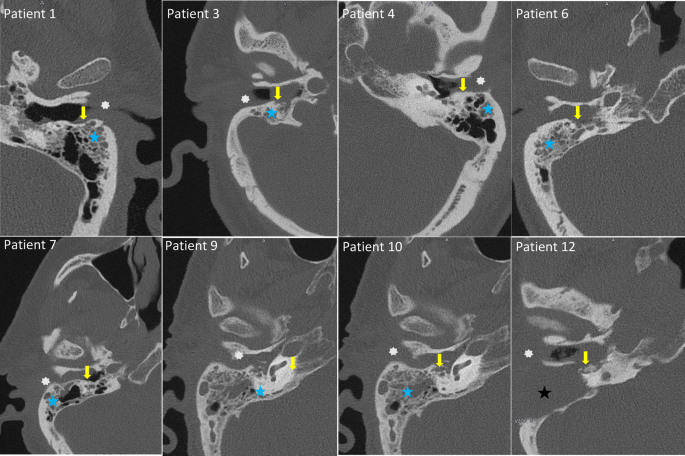

CT scans of the temporal bone, the most commonly used imaging modality in MOE according to the literature22, were available for analysis in 11 out of 13 patients and revealed erosions of the temporal bone and mastoid fullness, which is consistent with descriptions of other studies23. The goal was to gain an overview of the mastoid region and evaluate possible bony erosions that might strengthen the diagnosis of MOE.

The two patients who did not receive standard CT scans of the temporal bone received PET scans that revealed typical inflammation uptake in projections on the temporal bone in both scans. The two patients who received PET scans had complete facial nerve paralysis (HB °VI after House Brackman). One of the patients suffered from progressive nerve deficits of other cranial nerves in addition to the facial nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve and vagal nerve) in the course of the disease. PET scans were performed to rule out possible malignancy in these patients and to gain further insights into the anatomical extent of the disease.

CT-scans of eight patients included in the study. Typical radiological findings in patients with MOE as seen here are mastoid fullness (blue star, black star in patient 12 shows persistent fullness in the mastoid area after mastoidectomy), bone erosions (yellow arrow) and fullness of the external ear canal (white asterix).

Treatment

Systemic antibiotic treatment was documented for twelve out of the thirteen patients. Therapy was initially started as calculated therapy in all patients and was adapted further after microbiological assessment via ear canal swabs. Six out of the thirteen patients received only a single antibiotic. Three of those six patients received piperacillin/tazobactam, and the other three received ceftazidime. Antibiotic therapy, including therapies with ceftriaxone, meropenem, clindamycin, fosfomycin and vancomycin, was administered to all seven of the other patients during the course of the disease. Overall, seven out of twelve patients received ceftazidime during their treatment, and it was the most commonly used antibiotic.

Eleven out of the thirteen patients underwent surgical treatment. Ten of those patients received mastoidectomy. One of the patients who underwent mastoidectomy also received decompression of the facial nerve, one patient underwent partial petrosectomy due to advanced inflammation of the petrous bone, and one patient underwent total petrosectomy. One patient who did not undergo mastoidectomy received debridement of the external ear canal with removal of granulation tissue. The patient who underwent total petrosectomy had initially only undergone mastoidectomy; however, owing to the aggressive course of the disease, petrosectomy had to be performed as revision surgery.

Granulation tissue was found in all patients who received surgery, and tissue biopsies from all these patients were sent for pathology. All of the tissue samples were described as inflammatory granulation tissue, and no incidental findings, such as squamous cell carcinoma or other malignant diseases, were observed among the patients.

The average length of hospital stay was 26.2 days (5–57 days). Longer hospital stays were associated with revision surgery and/or prolonged antimicrobial treatments.

The follow-up treatment after the inpatient stay consisted of continuation of oral antibiotic therapy according to the recommendations of the infectiologists, clinical assessments and, if necessary, imaging controls. Referrals to diabetologists were made to ensure ongoing antidiabetic therapy and counseling. Most patients were treated with oral antibiotics for at least 10–14 days after the inpatient stay, some longer, depending on the length of antibiotic therapy during the inpatient stay. In total, we aspired to administer systemic antibiotic therapy for at least three to (preferably) six weeks.

Complications

Three patients were selected as small case reports for a more detailed description of the course of the disease:

Patient 1 was a male patient aged 72 years at MOE diagnosis. He suffered from otalgia and hearing loss since June 2018. The patient had already been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and had poor compliance with antidiabetic therapy (metformin). He was initially treated at an external clinic. Microbiological swabs were taken, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was detected. The patient was initially treated with ciprofloxacin ear drops. He developed increasing otalgia and facial nerve paralysis (initially °III after House-Brackmann) and thus received surgical debridement of the ear canal externally after four weeks of conservative treatment. After surgery, the pain decreased, but facial nerve paralysis persisted. The patient received oral ciprofloxacin for five weeks (500 mg twice a day), and the ear canal was cleaned twice a week. In January 2019, he presented at our clinic with increasing otalgia. At the initial presentation, the patient suffered from facial nerve paralysis °VI after House-Brackmann. The ear canal was not significantly swollen, but tympanic effusion was visible. Blood tests revealed only mildly increased inflammatory parameters (CRP 0.9 mg/dl), but HbA1c was severely elevated (11.6%). Microbiological swabs were taken, the patient was admitted, and calculated intravenous therapy with piperacillin/tazobactam (Tazobac 4.5 g four times a day) was initiated. CT scans revealed typical signs of mastoiditis with mastoid fullness, and bone erosions could initially not be ruled out. Antibiotic treatment did not relieve the patient’s symptoms after 72 h, and since the CT scan revealed mastoiditis, the patient underwent mastoidectomy and partial petrosectomy. Intraoperatively, it was observed that granulation tissue surrounded the facial nerve; the nerve was decompressed, and suspected tissue was sent for pathology for testing. Postoperatively, the pain subsided. Diabetes consultation was carried out, and the patient was put on insulin. Furthermore, we consulted infectious disease specialists. Long-term antibiotic treatment was recommended. The patient was discharged after 33 days at the hospital and received oral ciprofloxacin for four more weeks (750 mg twice per day). He presented at our clinic again one year later with otalgia of both ears. Both auricles were swollen and reddened, but the ear canals were inconspicuous. Purulent secretions from both auricles were visible and sent for microbiological testing. No pathogen was detectable. Blood tests revealed only mildly elevated inflammatory parameters (CRP 0,3 mg/dl) but an even higher HbA1c than the other results from 2018 (12.6%). A CT scan revealed no signs of mastoiditis, osteomyelitis or other pathologies, especially no recurrence of MOE. The clinical diagnosis of perichondritis of both auricles was made. The patient was admitted and received intravenous clindamycin (600 mg three times a day). Diabetes consultation was again carried out, and the patient was made aware of the urgency of antidiabetic therapy. The inflammation subsided, and antibiotic therapy could be switched to oral clindamycin after 7 days of intravenous therapy. The patient was discharged and received oral clindamycin for four more days. From then on, the patient was lost to follow-up. MOE did not recur in this patient after the inpatient stay in 2018 for at least 12 months.

Patient 2 was a male patient aged 80 years at the time of MOE diagnosis. He had suffered from otalgia and otorrhea since October 2016. He was known to have type 2 diabetes as well as diabetic neuropathy and nephropathy. The patient was on insulin. He initially presented to an ENT colleague in a private practice and received oral antibiotics (the name of the medication was not recalled by the patient). He then presented at the neurological clinic because of newly developed facial nerve paralysis (severity was not documented). He was transferred to our ENT clinic due to the associated otalgia and otorrhea. The patient initially presented with swelling of the ear canal and purulent secretions. Microbiological swabs were taken from the ear canal, which revealed the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Blood tests revealed only mildly increased inflammatory parameters (CRP 2,2 mg/dl), but HbA1c was elevated (9,8%). A CT scan revealed osteolytic destruction of the mastoid process on the right, with mastoid fullness and swelling of the external auditory canal and surrounding fatty tissue fibrosis, compatible with a chronic inflammatory, destructive process, possibly in the context of MOE. The patient was admitted and received ceftazidime (2 g three times a day), and surgery was performed four days after admission (mastoidectomy with facial nerve decompression) because of highly suspected MOE with bone erosion, Pseudomonas aeruginosa detection and facial nerve paralysis. Again, diabetes consultations was carried out to optimize antidiabetic therapy. The patient received ceftazidime for a total of 21 days. He was discharged from the ENT clinic with no additional signs of acute infection, neither clinically nor in laboratory tests. After discharge, he was lost to follow-up.

Patient 12 was a male patient aged 90 years at the time of MOE diagnosis. He had suffered from otalgia, hearing loss and bloody otorrhea since December 2015. No history of diabetes was known, but the patient suffered from tuberculosis in the 1950s. He received mastoidectomy and a tympanostomy tube in January 2016 in an external clinic with the initial diagnosis of mastoiditis. He presented at our clinic with persistent otalgia a few weeks after the initial surgery. Ear microscopy revealed swelling of the ear canal and secretion. There was no documentation of facial nerve palsy. Inflammation parameters were moderately increased (c-reactive protein 5.9 mg/dl). His HbA1c was not elevated (5.7%). A CT scan was performed, which revealed inflammatory granulation material reaching the petrous apex, bony erosion of the ear canal, and fullness of the ear canal after mastoidectomy was performed (see Fig. 2, Patient 12). Microbiological swabs of the ear canal were obtained, and calculated antimicrobial therapy with intravenous Ceftriaxone (2 g once a day) was initiated since the initial working diagnosis was insufficiently treated mastoiditis because of the absence of diabetes and not MOE. The patient received a complete diagnostic workup concerning possible tuberculosis, which was ruled out. Revision surgery was performed, and the ear canal and the mastoidectomy cave were filled with granulation tissue. A complete petrosectomy was not performed because the internal carotid artery was unprotected within the inflammatory tissue. After the microbiological swabs revealed the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, infectious disease specialists were consulted, and antimicrobial therapy was switched to intravenous fosfomycin (3 g three times a day) and ceftazidime (2 g three times a day) for a total of four weeks. Otalgia and otorrhea declined. A control CT scan revealed progression of the disease with inflammation along the skull base, the pterygopalatine fossa and the retropharyngeal space. Further surgical intervention was not considered useful or possible. Given the advanced age and disease of the patient, we decided against further intensification of surgical therapy in agreement with the patient and the patient’s family. The patient was discharged in stable condition and experienced improved otalgia. He received oral ciprofloxacin for two more weeks. Six months later, he presented with increasing otalgia. After new microbiological swabs revealed P. aeruginosa again, the patient received two additional weeks of intravenous fosfomycin and meropenem after consultation with our infectious disease specialists. Again, the patient’s otalgia subsided sufficiently, and the patient was discharged in satisfactory overall condition; this patient did not receive further oral antibiotic treatment. Eight months later, he again presented with increasing otalgia. Another round of intravenous ceftazidime and ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice a day) was given for a total of three weeks, again achieving satisfactory pain relief. The patient was again discharged in stable condition and subsequently lost to follow-up.

In conclusion, two surgeries were performed, the second of which revealed that inflammation progressed too far to achieve disease control via surgery. The patient received a conservative, nonsurgical treatment approach after the second surgery, and the control CT scan four weeks after this surgery revealed further disease progression. Antibiotic therapy ensured very effective symptom control over several months after each course. Nonetheless, controlling or even curing MOE was not possible in this case. Interestingly, the patient had no diabetes or other forms of immunosuppression.

Leave feedback about this